You

are taking a test tomorrow. Your

teacher was generous enough to allow you to

bring a cheat-sheet, but only on one side of an A4

paper. How would you arrange the overwhelming

amount of information you need to know and

pack them in a space so limited? Naturally, you

would miniaturise your writings, compress your

equations and facts and cram in as much as you

can. Still, eventually you would reach the edges

of the paper, no longer able to smuggle those last

few equations into the exam hall.

And this, indeed, is the million-dollar question

of our information age.

The advent of the d ig i ta l age has seen

explosive growth in the complexity

and var iety of data. More

than a billion gigabytes of

new data are created

each day [1], a pace

u n m a t c h e d b y

t he advance s i n

information systems.

Data centres and

s e r ve r s t a ke u p

large spaces and

c o n s u m e e v e n

more energy each

year. Thus, ensu r i ng

each bit takes up the

minimal amount of space

i s paramount. The ultimate

so l ut i on? Cod i ng i nfo rmat i on at

the

atomic level, as Feynman envisioned nearly 60

years ago.

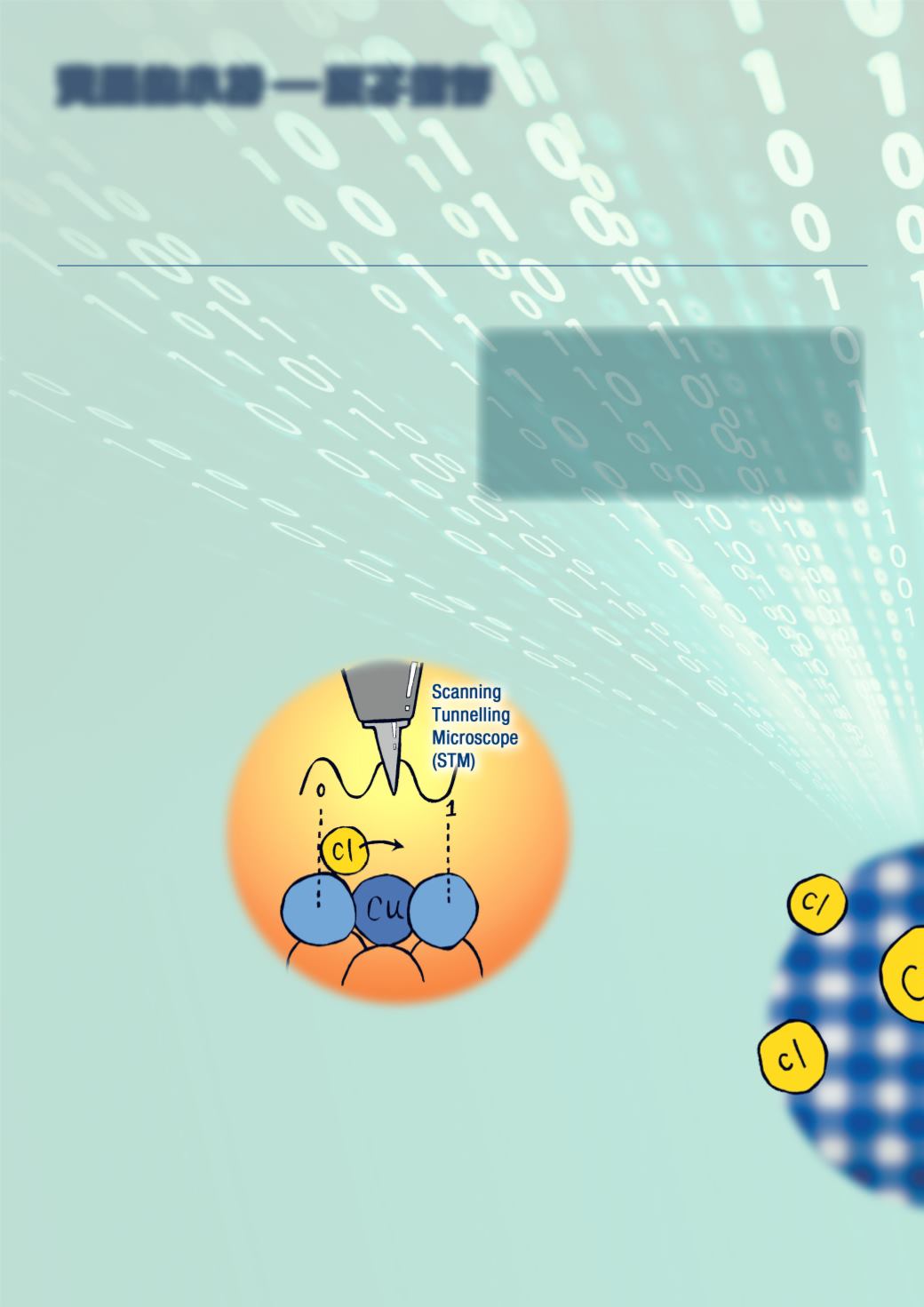

Scientists at Delft University have approached

the physical limit by reducing each bit to single

atoms. By arranging individual chlorine atoms in

an exactly ordered pattern, the research team

built a memory of 8000 bits (1 kilobyte) on an area

as small as 100 nm wide [2]. The hard drive was

assembled by coating a chlorine atom lattice

on a copper surface in ultrahigh vacuum, with

the precise locations of each individual atom

manipulated by injecting an electric current using

a Scanning Tunnelling Microscope. The presence

of a current allows the chlorine atoms to switch

places, res

sites and occupied sites. Each vacant site is

only 20 to 30 pm deep.

These combinations of vacant sites

(V) and occupied sites (Cl) come in

two distinct configurations, V-Cl and

Cl-V. Translated into binar y, they

can be represented as “0” and “1”,

for different numbers, letters and

symbols of data.

A d e n s i t y o f 5 0 2

t e r a b i t s p e r s q u a r e

inch was achieved, an

unprecedented density of

data that is 500 times higher

than the best commercial hard

d i sk ava i lab l e on the mar ket

[1]. To put that into perspective,

the entirety of the US librar y of

Congress can be stored within a

0.1 mm wide cube. Furthermore, the

atomic-scale device employs atoms

by removing them f rom a uniform

surface as opposed to employing atoms

in an additive manner, profoundly reducing

errors.

By David Iu

姚誠鵠

費曼的小抄-原子儲存

Feynman’s Cheat Sheet

–

Atomic Storage

Why can't we write the entire 24

volumes of the Encycolpaedia Brittanica

on the head of a pin?

— Richard Feynman,

“There’s Plenty of Space at the Bottom”, 1959