Page 7 - Science Focus (Issue 017)

P. 7

現象亦出現於其他帶有甜味的物質,例如葡萄糖、蔗糖和阿斯

巴甜。

警告:不要在你的學校實驗室裡嘗試!

然而,有研究亦指出糖精可以啟動舌頭上其他的感受器,包

括 T2R 苦味感受器和香草第一類受器(TRPV1)。這分別是糖 雖然觸摸和輕嚐實驗室裡各種化學品和生物樣本的想

精帶有苦味和金屬味餘韻的可能原因 [11]。 法可能十分誘人,而你可能因此取得重大發現……可是

作為第一隻推出市場的人工代糖,糖精(Sweet’N Low ) 大多數的化學物質都不宜進食或用手直接接觸。在實

TM

啟發了同類產品的發展,像是阿巴斯甜(Equal )和三氯蔗糖 驗室內,我們應該戴上手套,並在實驗後把雙手徹底

TM

(Splenda ),這些產品在味道上都經過改良。近年亦流行著

TM

糖醇(赤藻糖醇、木糖醇等)和植物提取物(甜菊糖、羅漢果糖 洗淨。最重要的是:不要吃下任何實驗用的化學品!

等)這些被標榜為較健康的天然代糖。消費者應該為今時今日

市面上琳瑯滿目的代糖選擇感到滿足,因為這能使我們嚐到甜

味的同時,免受體重增加和患上糖尿病的風險。

1 Sulfobenzoic compounds: Compounds containing a

sulfoxide group attached to a benzene ring (Ph–SO2R)

磺基苯化合物:一個類別的化合物,包含一個帶有苯環的亞碸

(Ph–SO2R)

2 Patent: A right or ownership to protect a certain invention

by preventing others from making, using and selling it, which

usually lasts 20 years from the filing date.

專利:對一個發明的擁有權,可以透過防止別人製造、使用和售賣,從而保

護相關發明。有效期通常為由申請日起計的二十年。

3 Hydrogen bond: A relatively weak, non-

covalent intermolecular interaction between

an electronegative atom (N, O, F) and the

hydrogen atom covalently bonded to another

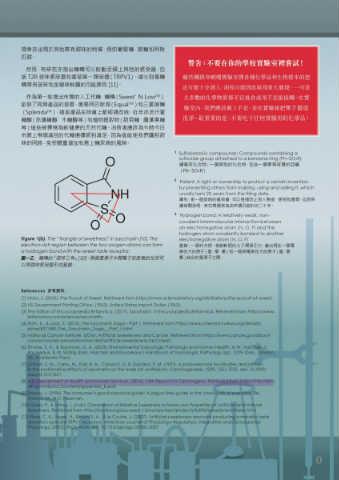

Figure 1(b). The “triangle of sweetness” in saccharin [10]. The electronegative atom (N, O, F)

electron-rich region between the two oxygen atoms can form 氫鍵:一個非共價、相對較弱的分子間吸引力,會出現在一個電

a hydrogen bond with the sweet taste receptor. 負性大的原子(氫、氧、氟)和一個與電負性大的原子(氫、氧、

圖一乙 糖精的「甜味三角」[10]。兩個氧原子中間電子密度高的位置可 氟)結合的氫原子之間。

以與甜味感受器形成氫鍵。

References 參考資料:

[1] Hicks, J. (2010). The Pursuit of Sweet. Retrieved from https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/the-pursuit-of-sweet.

[2] US Government Printing Office. (1963). United States Import Duties (1963).

[3] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2017). Saccharin. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.

britannica.com/science/saccharin.

[4] Roth, K., & Lück, E. (2015). The Saccharin Saga – Part 1. Retrieved from https://www.chemistryviews.org/details/

ezine/8271881/The_Saccharin_Saga__Part_1.html

[5] National Cancer Institute. (2016). Artificial Sweeteners and Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-

cancer/causes-prevention/risk/diet/artificial-sweeteners-fact-sheet.

[6] Elmore, S. A., & Boorman, G. A. (2013). Environmental Toxicologic Pathology and Human Health. In W. Haschek, C.

Rousseaux, & M. Wallig (Eds), Haschek and Rousseaux's Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology (pp. 1029-1046). London,

UK: Academic Press.

[7] Cohen, S. M., Cano, M., Earl, R. A., Carson S. D. & Garland, E. M. (1991). A proposed role for silicates and protein

in the proliferative effects of saccharin on the male rat urothelium. Carcinogenesis, 12(9), 1551-1555. doi: 10.1093/

carcin/12.9.1551

[8] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). 14th Report on Carcinogens. Retrieved from https://ntp.niehs.

nih.gov/ntp/roc/content/appendix_b.pdf.

[9] Emsley, J. (1994). The consumer’s good chemical guide: A jargon-free guide to the chemicals of everyday life.

Oxford, UK: W.H. Freeman.

[10] Guley, P., & Uhing, J. (n.d.). Comparison of Relative Sweetness to Molecular Properties of Artificial and Natural

Sweetners. Retrieved from http://shodor.org/succeed-1.0/compchem/projects/fall00/sweeteners/index.html

[11] Riera, C. E., Vogel, H., Simon, S. A., & le Coutre, J. (2007). Artificial sweeteners and salts producing a metallic taste

sensation activate TRPV1 receptors. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative

Physiology, 293(2), R626-R634. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00286.2007

5